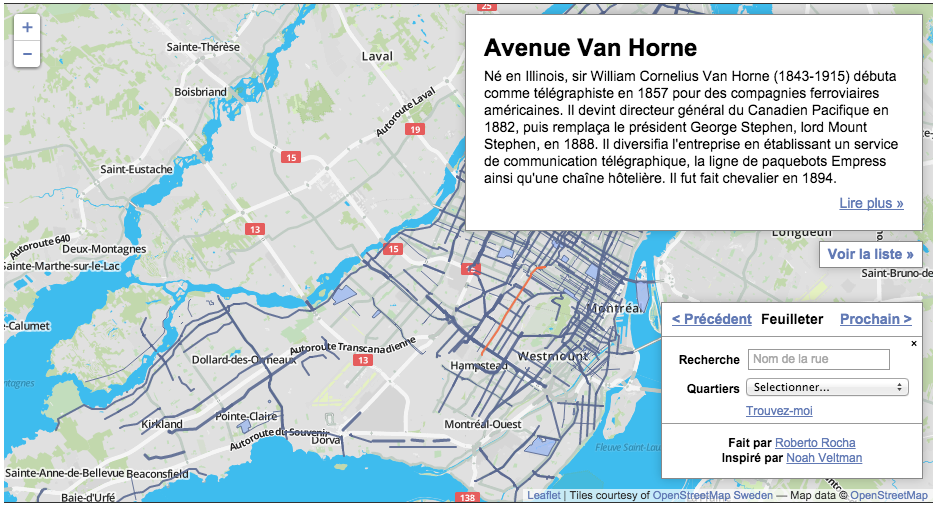

Click here to see the map at Huffington Post Québec

First of all, a clarification. I did not really make that map. I adapted the code from Noah Veltman’s San Francisco history map, and made one for Montreal. Compare both maps, and you’ll see they are very similar in many ways.

That said, the data sources between the maps are completely different, as are the choices of data structure and querying. That’s what I talk about here.

Scraping the toponymical data

WARNING: the government of Quebec has a copyright notice on all its websites, and protects government data the same way it protects books and musical works. I obtained permission from the Commission de toponymie to use that data.

The Commission de toponymie, part of the Office québécoise de la langue française, has a large online database of just about every place name in Quebec. Just the set for Montreal contains more than 8,000 entries for streets, parks, buildings, and other places.

Like many government databases, the full data is not available for download. A general search returns results over several pages, which means it can be scraped.

The website uses AJAX to render the results of a page, which means it cannot be scraped from its source code alone. This is a job for Selenium, a Python library that can simulate a human user clicking on buttons and filling forms. The results of those actions, which render in the browser, can then be scraped.

I used Selenium to return just the entries for Montreal, paginate through the pages of results, and find the ID for each entry. Then I used requests and BeautifulSoup to access and scrape each entry.

I skipped all streets with number names (1ère Avenue, etc.), since these have no histories. After scraping, I also removed all entries with saint names, since these aren’t specific to Montreal. In the end, I ended up with close to 4,400 entries, for streets, parks, buildings, everything! in a CSV.

The code for the scraper can be found here.

Getting the street polylines

The City of Montreal’s open data portal has an excellent dataset called Géobase. It has every street in the city, split into segments for each intersection. It also happens to be a great geocoding tool, since every segment contains the number addresses on both ends.

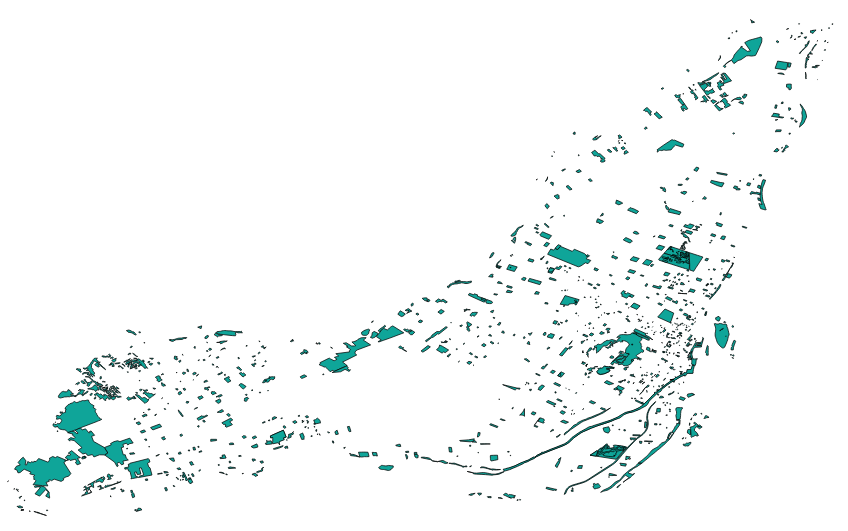

It looks like this, loaded into QGIS:

That shapefile has thousands of streets. Since I wanted to create a flat HTML file with geoJSON data (no app servers for me, please), I had to be picky. Leaflet can handle around 400 features before browser performance starts to suffer.

But what roads to pick? What to leave out? This is an editorial and philosophical decision. I decided to go with major roads that most Montrealers know about (Jean-Talon, Sherbrooke, Acadie, etc.) as well as streets that share names with métro stations. These names are part of the daily lives of many citizens.

For the first problem: The Géobase, fortunately, has a field with the classification of streets: highways, major arteries, secondary arteries, local streets, etc. I filtered out the major streets.

But smaller streets also have names of important historical characters, and of métro stations. This required a lot of manual work to pick out the right ones using QGIS.

I was left with close to 600 street names.

Since I needed full streets, not segments, I used QGIS to dissolve (merge) the segments based on the street name. This worked, but resulted in some multi-part polylines, as there are streets that share the same name in different parts of the city. This involved manual cleanup.

Getting the park polygons

I also wanted to include some parks in the map, but the City does not offer a shapefile of parks as open data. A shapefile I did obtain of all green spaces did not include their names.

So I went to OpenStreetMap, downloaded all data for Montreal from the excellent site Metro Extracts, which lets you do just this for hundreds of cities.

The natural features for Montreal looks like this:

But being fed by the public, the data for parks had a lot of inconsistencies, spelling errors, and few parks had names. Again, I had to be picky. I chose the largest parks on the island, and parks whose names have changed recently to honour recent Montreal luminaries. Other park names I had to add manually (like Oscar Peterson Park in Little Burgundy, which was still called Campbell Park). I ended up with about 40 parks.

Joining the data

As large as the Toponymie database is, it doesn’t have historical data for many streets and parks. Although the name is listed in the database, the entry is blank (curiously, a significant number of English names have no historical data).

So when it came time to join the historical descriptions to the shapefiles, many had to be discarded due to missing data. Only about 250 streets and 25 parks were successfully joined.

This is the final shapefile I was left with:

I exported the streets polylines and parks polygons as geoJSON separately, the number ID of the street (same as the unique ID of its Toponymie entry) then joined them into a single feature collection using geojson-merge, a handy command-line tool from MapBox.

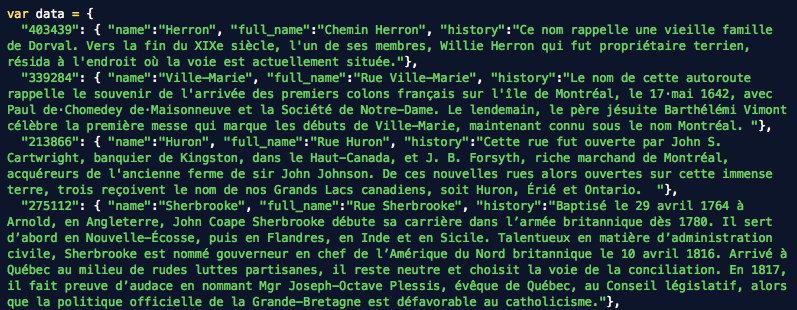

The historical data was made into a JSON dictionary with the number ID as keys, using the excellent Mr. Data Converter.

Editing the histories

Certain entries, like Hochelaga, are huge, too big for web display. So I set a hard limit of 500 characters and edited down all the entries that passed it. If people want to read the full entry, I included a link to it from the history pane.

Visualizing the streets

For this, I left Noah’s JavaScript code do most of the heavy lifting. I had to modify one major mechanic: Noah used hash-based navigation to switch between features. Although I was using unique IDs to query the historical data based on the same ID of the feature clicked, the geoJSON file does not allow such a direct connection.

So I used a little hack. To get the history from clicking on a feature, accessed the the unique ID deep inside the Leaflet object of that feature, then called the history file on it.

For the navigation from the right menu or the browsing buttons, I looped through the entire geoJSON file until it found a matching ID, then displayed that history. I thought this would slow down the navigation, but no, it happens very quickly.

In the end, the map had fewer streets and parks than I hoped for, but enough to spend a long time learning about Montreal’s most important place names.

In the Early 1900’s there was a street in Montreal called German Street. Do you know what it is called now?

According to “Les Rues de Montreal”, German/Germaine street is now l’Avenue de l’Hotel de Ville.

Interesting project – merci.

Cool. Sadly, the map is no longer at the link, although the story is. Or I am just missing it. It is in French, but the translation is clean in Chrome.

Sadly, the link is broken on the HuffPost site. Bu you can see a backup here.