This is the text of the keynote speech I delivered at the 2018 Concordia Library Research Forum. It has been edited slightly.

Thank you for this lovely opportunity to be among you this morning.

I feel especially honoured to deliver this keynote because I believe librarians and journalists share a special kinship because our jobs and our missions in life are very similar.

Let me explain.

I’m a data journalist. That means that I write news reports using spreadsheets and databases as raw materials, rather than interviews and documents. Often that data is publicly accessible. In other times, I have to request it repeatedly. Sometimes I take the government to court to get data that could embarrass them.

After I obtain the data I have to prepare it, analyze it, filter it, and present it in an interesting way that most people can understand.

Here are some examples.

Every time the census comes out it’s like Christmas for data nerds. There are thousands of stories waiting to be mined in census data, and this was just one that I did: how Canadians are more bilingual than ever before and it’s mostly driven by Quebec.

Sometimes I obtain data from the city of Montreal, like a record of all the water main breaks over the past 18 years. Then I look for the chronic hotspots and try to explain why some areas are more problematic than others.

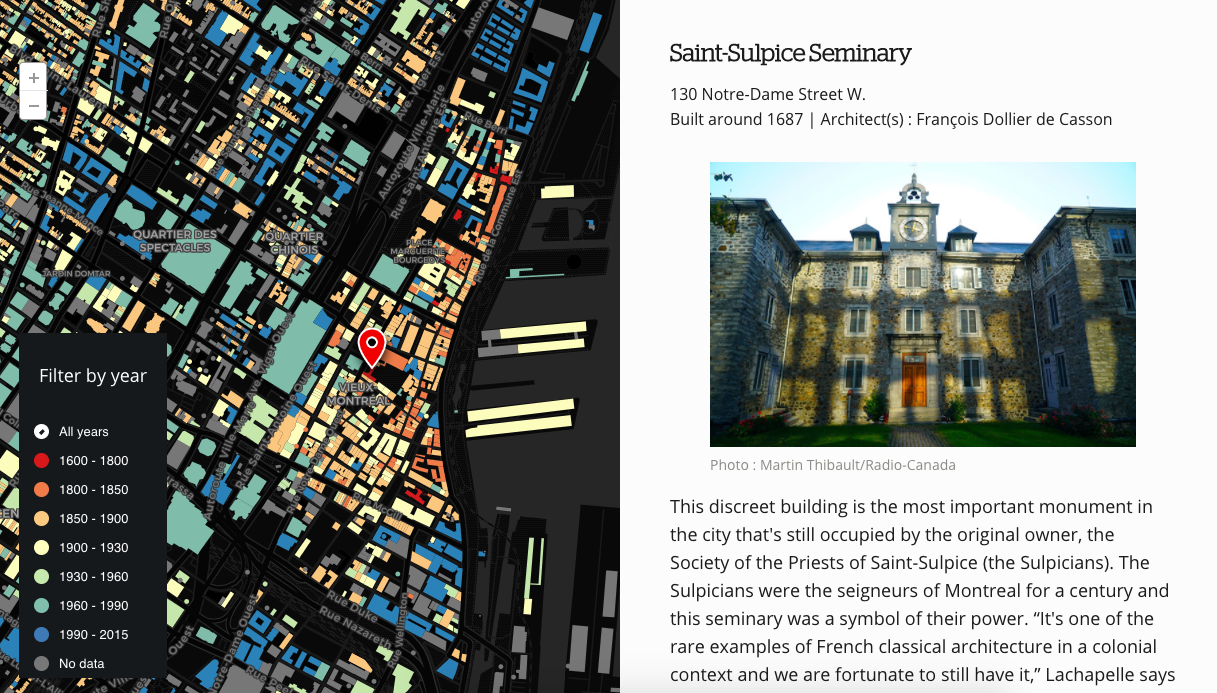

Sometimes my work is simply to make publicly available data accessible and educational. Here I took tax assessment data, which has the year of construction of almost all buildings in Montreal, and made a map, where the buildings are coloured by how old they are.

We used this to take readers on a trip through Montreal’s architecture history, and let them explore the map on their own.

–

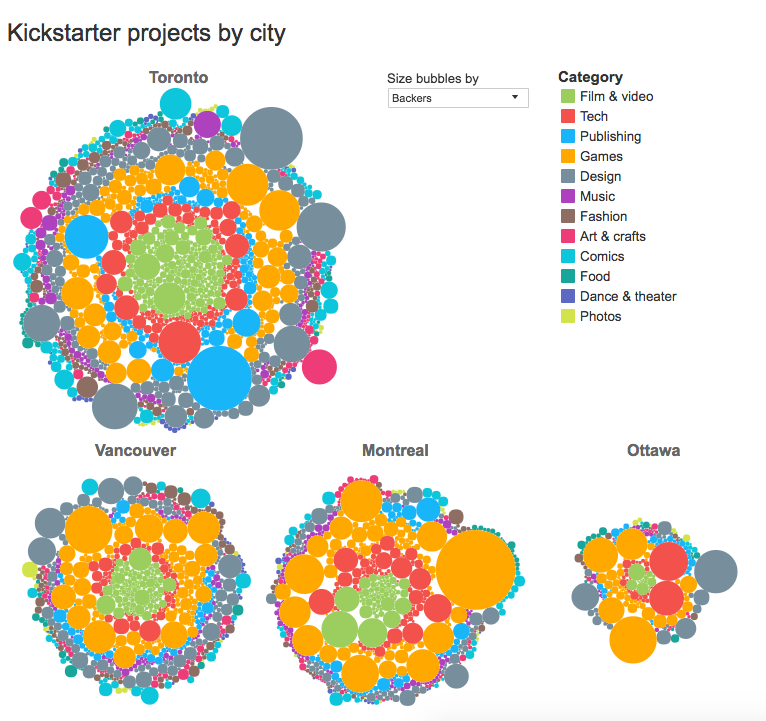

I also use data to reveal interesting facts about Canadians. I was curious to see if there were regional differences in the kinds of projects Canadians launch on Kickstarter. So I visualized that data by city. And sure enough, we see that Toronto tends to be more entrepreneurial with tech and design, while Montrealers excel in video games, and Vancouver is big on films.

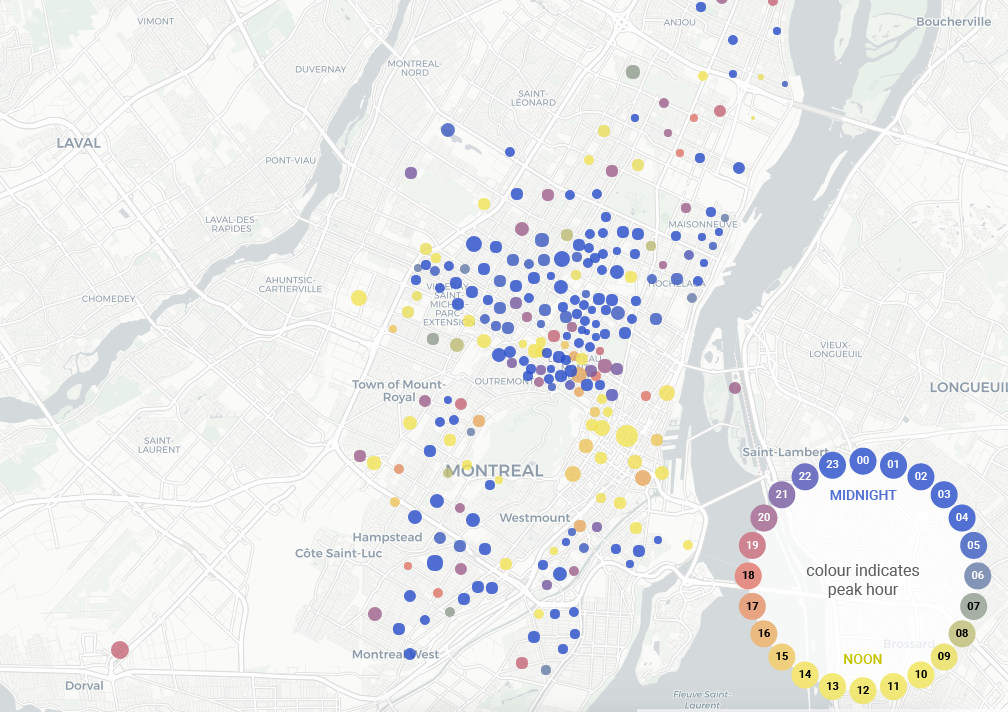

Sometimes I collaborate with data scientists and statisticians when the data is complex. I was curious to see if car2go cars in Montreal were taking up street parking meant for residential permit holders. This was inspired by a resident of Mile End who scolded me when I parked a car2go in front of her triplex.

So I wondered if the data could show if this was a bigger problem.

I harvested three weeks of real-time locations of car2go cars, and a talented data scientist I know ran some clustering algorithms on it. Sure enough, we found that car2go cars tend to cluster in Mile End during work hours. Those are the yellow spots in the middle of the map.

When we went to see for ourselves, we saw shared cars taking up a whole street and annoying the locals. This exposed for us possible urban planning and transportation problems. What is it about the transit options to Mile End that are causing so many to take these cars there?

Enough about me. Let me share some impressive projects from my peers.

When the data doesn’t exist, sometimes you have to create it. There’s no comprehensive data on fatal shootings by police officers in Canada. So my colleague Jacques Marcoux in Winnipeg spent months asking every police force in Canada for their fatal encounters. For the first time we Canada, we had a national searchable database of police victims.

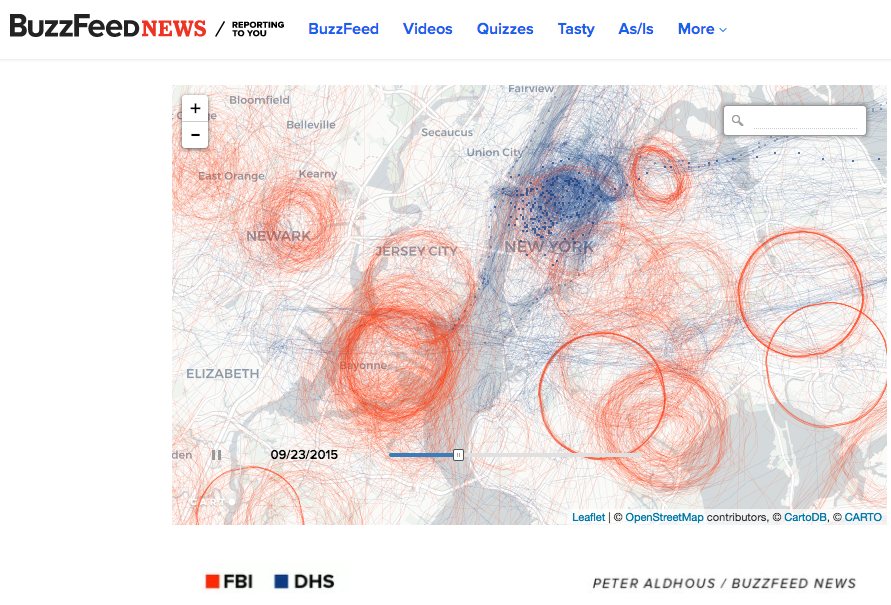

Some data journalists are using cutting-edge technology to tell original stories with data. Buzzfeed used machine learning to identify US government spy planes among hundreds of thousands of flight radar records. This would not have been possible with traditional research means.

And some outfits, like ProPublica, are positioning themselves as watchdogs of these cutting edge technologies. Police forces in the US are increasingly using algorithms to assess the risk of repeat offenders. ProPublica found that these algorithms were giving black men higher risk scores than white men even if they have similar criminal records.

By reverse-engineering these algorithms they learned that the data used to train these models is biased — because blacks were overrepresented in the training data.

All of these examples share something in common. They all take this bounty of data that we’re drowning in and make sense of it using statistics, computer science, and visual design. They craft human-interest narratives out of rows and columns, which not everyone knows how to work with.

So I hope I showed you how journalists and librarians have similar missions. Our jobs are to collect and organize information, and make it useful and accessible for the public. We both strive to create better-educated citizens who can contribute to a prosperous society.

And in this age of information overload, of competing sources and formats, and of increasing confusion about what is real and what is fake, our respective missions are more needed than ever.

So it’s in this spirit of kinship that I would like to start this day by doing another thing that journalists do really well: depress you to your very core with a bunch of really dreary, dispiriting facts.

We’ve all heard that we live in a post-truth world with plummeting trust in media and institutions. I’d like to show just how bad this is.

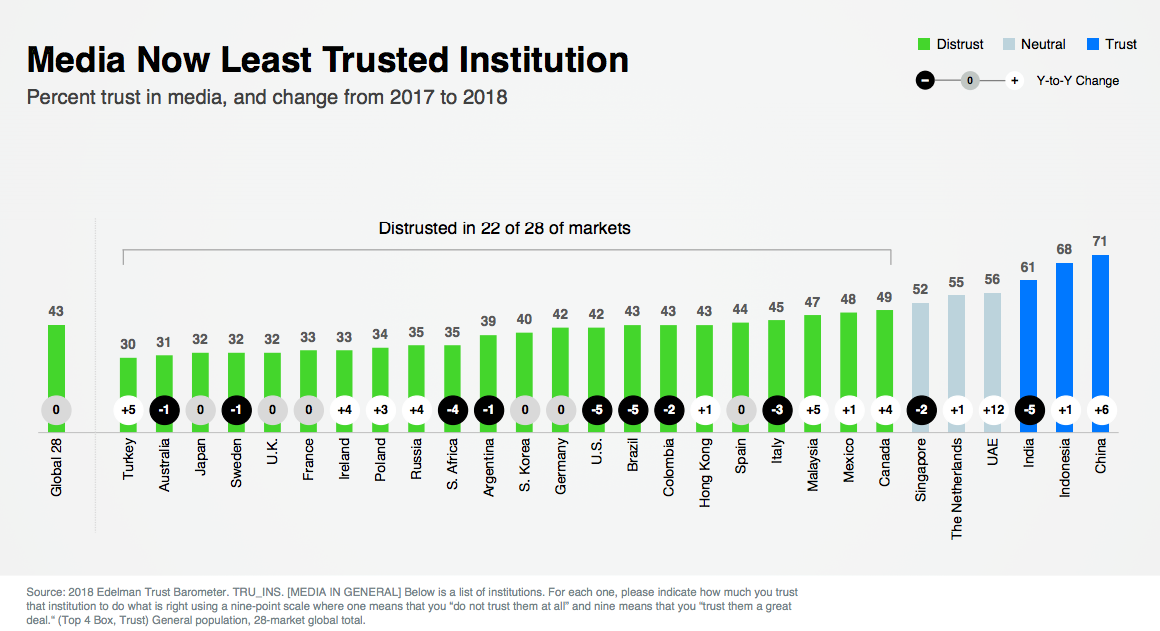

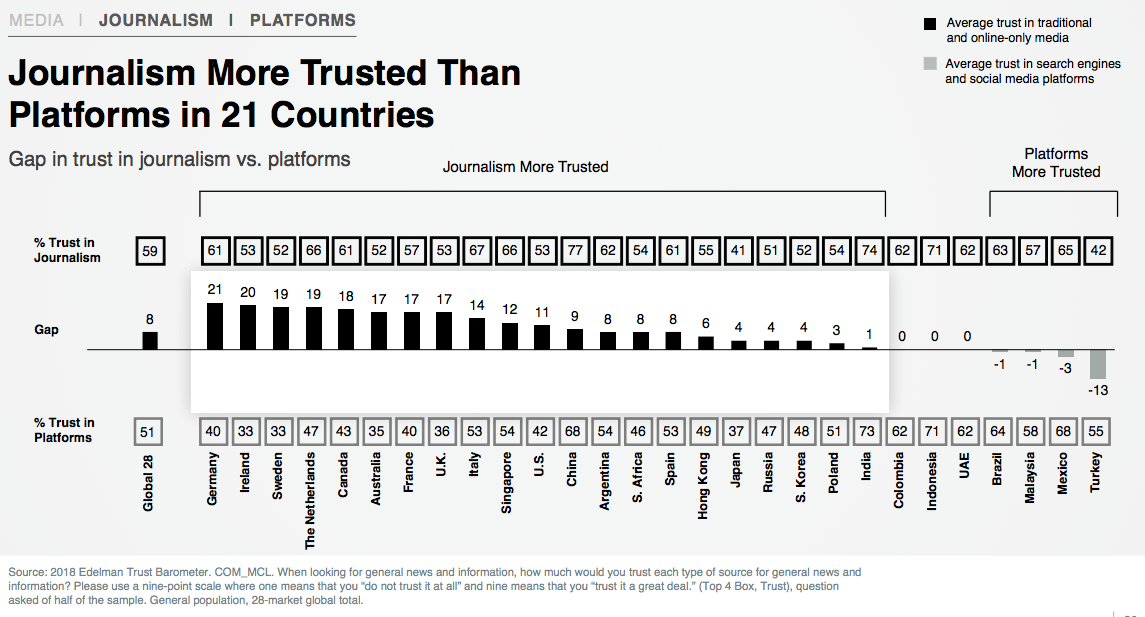

In the latest Edelman Trust Barometer, a global survey of 35,000 people, media was found to be the least-trusted institution in 22 countries, including Canada.

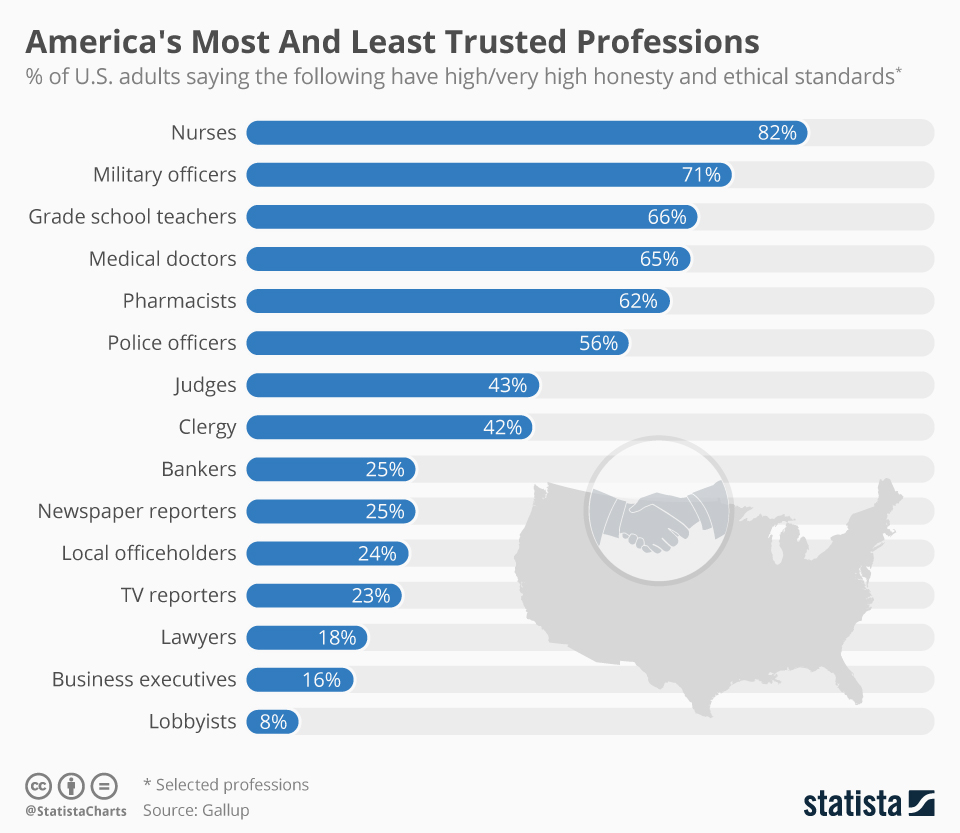

Likewise, journalists continue to rank among the least trusted professions, down there with lawyers and local politicians, according to a Gallup poll in the U.S.

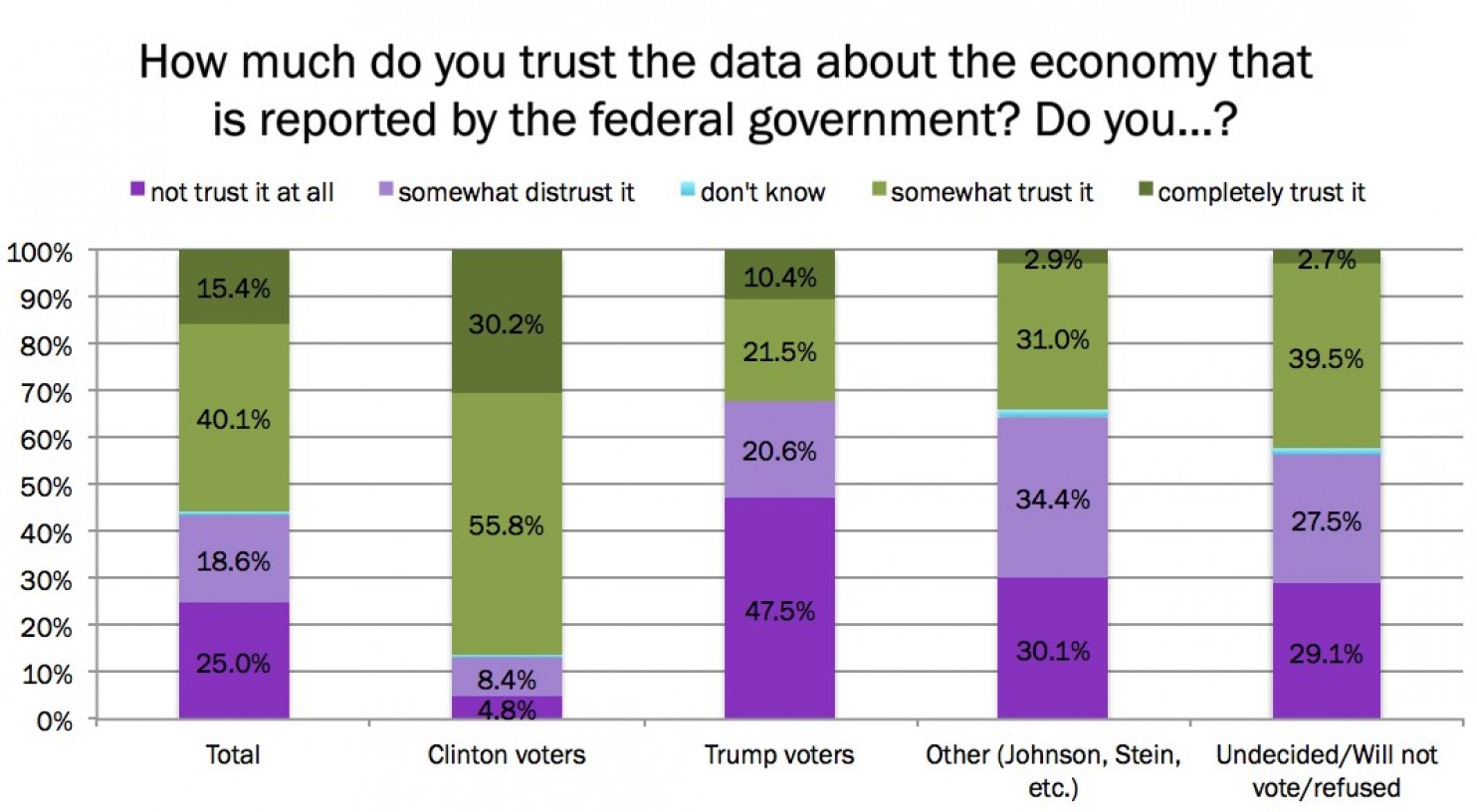

Add to that the declining trust in evidence-based statistics to the benefit of emotion-fuelled populism. A Marketplace-Edison Research Poll in 2016 showed that nearly half of Americans don’t trust official government figures, whether it’s unemployment, inflation or immigration stats. Among Donald Trump supporters that number jumps to 68%.

In the UK, 55% of the population believe the government is hiding the truth on things like the number of immigrants in the country, according to YouGov and Cambridge University.

Somehow, truth lost its lustre. It’s no longer sexy. In many cases, the truth just can’t compete with juicy rumours or straight up false information. Nowhere is this as evident and observable as in social media.

Multiple studies have shown that people share hoaxes far more widely than any fact-checking article that debunks it.

One study looking only at Twitter showed that a false story reaches 1,500 people six times quicker, on average, than a true story does.

In this study, a boring true and verified news story couldn’t chain together more than 10 retweets. A fake news story, on the other hand, could put together a retweet chain 19 links long—and do it 10 times as fast as accurate news.

Soroush Vosoughi, a data scientist at MIT who authored this study, said the following with understandable pessimism: “It seems to be pretty clear that false information outperforms true information.”

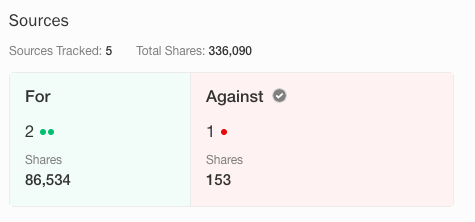

You can see this in the hoax-tracking website Emergent, created by Craig Silverman, one of the foremost experts on fake news. Today he’s an editor at Buzzfeed News.

The website counts how many times a false rumour was shared, and compares it to the performance of the factual story.

Item after item shows that the fake news story is shared and talked about far more than any article debunking it.

Caitlin Dewey, a reporter at the Washington Post, used to write a great column called “What was Fake on the Internet this week”. She stopped writing it in 2015. She said it just felt like a pointless endeavour because it wasn’t making a difference.

So what are we to do in this discouraging climate? What’s the point of sticking to our missions as truth-seekers if the truth falls on deaf ears? How can we operate in a world where opinions and feelings are seen to be just as valid as facts?

Did I depress you enough? Well, I didn’t come here just to ruin your day. I’m also here to tell you it’s not all gloom and despair. There are a few indicators out there that should give us hope, that tell us our vocations are not a losing battle.

And this is where I assume my other role as a journalist. Presenting alternatives and potential solutions.

But first, let’s do some difficult soul-searching.

A lot of this resistance to stats and facts is born out of a backlash against elitism. And in some ways, we can be insufferable elitists. There’s something arrogant and condescending about lecturing people with numbers, as if the complexity of humanity can be vulgarized with a percentage.

When we tell skeptics that immigration is good for the economy, or that crime is going down — and we have numbers to prove it — sometimes it just doesn’t register. Because in the end it might not correspond with their perceptions and experiences.

And in the battle between an impersonal number and a deeply-held conviction, guess which one wins?

Maybe you heard of the backfire effect. It’s when a person with strong beliefs is challenged by contradicting evidence, and instead of changing those beliefs, they just get stronger. It’s a defense mechanism: when your convictions are tied to your identity, attacking a conviction is like attacking the identity. So to protect that identity, people raise walls and double-down on a belief, even if it’s wrong.

And so people might be inclined to believe numbers are manipulated to push an agenda. And sometimes we dismiss them as uneducated rubes or conspiracy theorists. And this only reinforces the idea that we’re high and mighty elitists.

Journalists are guilty of this. Scientists are guilty of this. I have been guilty of it numerous times.

As people close to the original source of information, it’s easy to say, “Trust me, I know the facts. You don’t. Now shut up and listen.” And this may have worked in the past, when education and journalism were one-way lectures. But that was before everyone had access to information on the phones they carry in their pockets at all times. Before anyone could also broadcast information they witnessed or were privy to.

This doesn’t work anymore, and we’re slow to realize this. Many journalists still haven’t accepted that we no longer have a monopoly in access to audiences. Many still believe that journalism is the first draft of history, when tweets have taken that role.

And let me share a dirty little secret of journalists. Many of us have outright disdain for our audiences. You might catch us in an unguarded moment call them the great unwashed masses, or that they are idiots with no good ideas.

This culture of disdain is not universal, but it is common enough. It has a logical root. Often, when we hear from readers, it’s usually hate mail. The most motivated people who reach out to newsrooms tend to be the most disgruntled. They’re folks with an axe to grind.

So it’s natural that over time, journalists come to believe that these nuisance complainers ARE the audience. And this only aggravates this cultural separation between the press and people it serves.

I imagine it’s the same among scientists who only hear from science deniers and other malcontents.

So here we are. Caught in a dysfunctional but co-dependent relationship where we are only communicating via insults and accusations.

But what scientists and journalists may have broken, we can also fix. And many are starting to fix it.

And this is the point in my speech where things start to look up. Like any journalist, I’m a crusty cynic, but it’s only because deep down I’m a frustrated optimist. And that optimist is annoyingly stubborn.

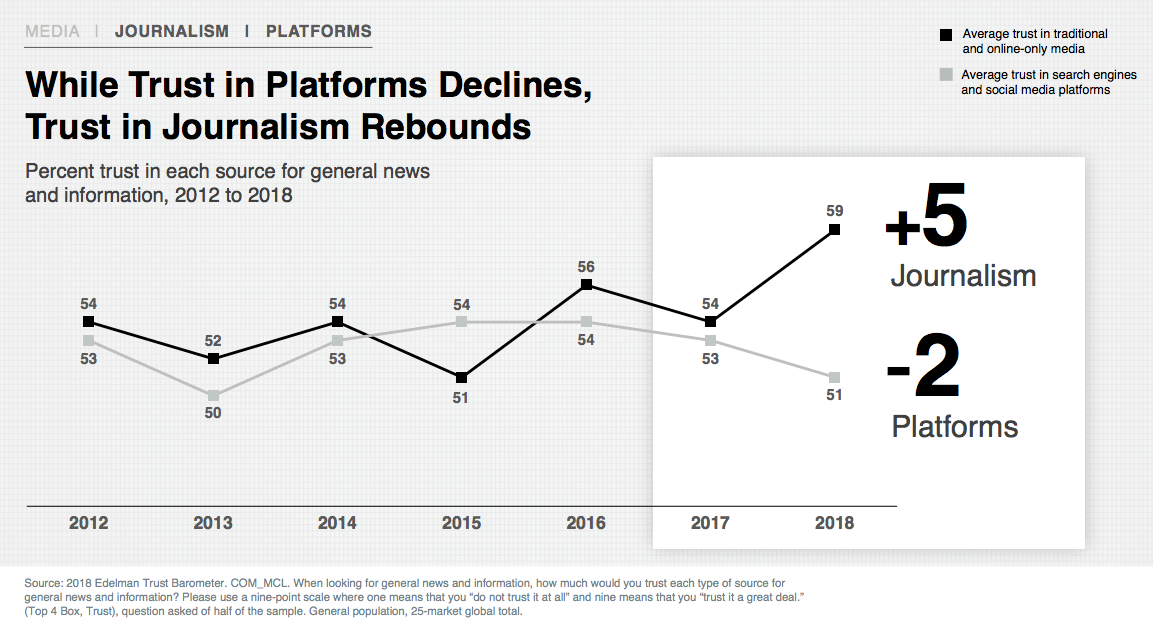

Remember that Edelman report on trust I mentioned earlier? Well, I only told you part of the story. Media might be the least trusted institution, but that depends on how you define media. That survey grouped journalism and social media platforms under the umbrella term “media”. But when they broke it down, a different picture emerged.

Trust in social media has been decreasing over the past few years, but trust in journalism is actually rebounding. And this is happening in many countries.

It’s almost as if the informational chaos of the internet is causing a backlash, and the public is once again hungering for authoritative sources of information.

And that thing I said about the backfire effect? It’s not as prevalent as some folks believe. There’s actually very little research on it, and it’s been hard to replicate in other studies. In fact, some studies have shown the opposite: that people do change their minds when presented with evidence, as long as it’s done respectfully.

The think tank British Future wanted to convince Britons that immigration is good for the country, and they had a bunch of economic figures to prove it. But all that quantitative evidence did nothing to sway minds.

People felt talked down to. Disrespected. As if the think tank thought they were stupid.

But you know what worked? Stories. Stories of immigrant families who succeeded, who are model community members and who contribute to their society. Test subjects responded warmly when they were shown photos of diverse communities going about their lives in social harmony.

It was the qualitative evidence that worked.

I quote from the report:

“When the intention is to engage with general, non-specialist audiences, there is no substitute for going and talking to the people with whom these arguments are designed to connect.”

Talking. Conversations. Exchanges. Not lectures. Not looking down on them. Not dismissing them. But trading stories.

And this is where journalists shine: we’re factual storytellers at heart. We turn facts and claims into narratives because we know that this is what humans are programmed to respond to. Not statistics, but stories.

We’re literally wired for this. Since we were cavemen we sat around fires telling stories. Our brains light up in completely different ways when we’re entranced by a good story.

As a data journalist, I live at an interesting intersection of stats and narrative. I take data created by governments, academics and non-profits and turn them into human stories that connect with people.

It’s not enough to throw data at an audience and expect them to see the facts. I have to reveal the human side of the numbers if I have any hopes of building a rapport with readers.

And this where some of the most exciting experiments in trust-building are taking place. Inside newsrooms. Journalists are realizing that just doing good journalism is not enough. And I want to share with you some of the initiatives being done.

As journalists, we demand transparency from politicians and other powerful figures. But we’re not very good at being transparent ourselves. This is changing. More newsrooms are opening up, inviting readers in, either literally into the newsroom or in the ways they operate.

The Guardian in the UK has been a pioneer in this. Since the last decade they have been repeating the message that journalists are not the only experts in the world. Their open journalism strategy reminds readers of this constantly, and they regularly involve them in reporting the news.

This strategy is driven by two main questions:

- Who knows more about this than I do? Can you help?

- Who knows less than I do? What do you want to know?

In 2009 they created a searchable database of MP’s expenses and asked their readers to help them make sense of it. It was a resounding success. Over 20,000 volunteers searched more than 170,000 documents, sharing what they found.

This encouraged The Guardian to repeat the exercise with many other investigations.

Oliver Laughland, a senior reporter at The Guardian U.S. said this:

“The journalists who work here have this ingrained in their consciousness. We’re always trying to think about ways in which you can engage with the audience and make them part of it.”

It’s no surprise The Guardian is also a leader in data journalism. Much of these initiatives are coming from data journalists themselves.

Take Buzzfeed News, The Los Angeles Times, and ProPublica in the U.S. They took a cue from scientists and started publishing the data and the computer code that they used to analyze it. They’re saying: here’s how we arrived at our conclusion. Feel free to try it yourself and challenge our methodology.

This is making journalism reproducible, transparent. It’s a conscious attempt to counter the belief that journalists have an agenda, that they make things up to please a cabal of corporate masters.

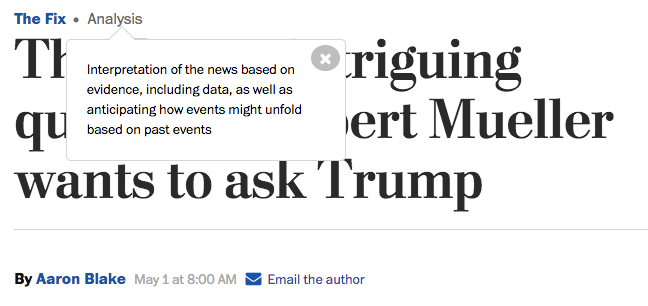

Or take the Washington Post. Few major outlets I know are making the effort to help their readers understand how a newspaper works.

For example: on analysis pieces, a little popup explains that analysis is a personal interpretation of the news based on evidence. In other places, they take pains to explain the difference between a column, an editorial, and hard news.

Bad faith attacks on the press have relied on public misunderstanding on these nuances. You may have heard of Project Veritas. This is an outfit in the US that takes undercover candid videos of journalists and edits them to make it seem like they have a political bias.

In one case, it secretly filmed a Washington Post reporter talking about the editorial stance the newspaper takes on certain topics, and how it’s separate from news and analysis.

For journalists and other media-literate people, this separation between hard news and opinion needs no explaining. But we’ve been wrong to assume all this time that everybody knows this, too. To a lot of people, a news story has the same weight as an opinion piece. An editorial attacking a politician is the same as the entire press attacking that politician.

This Twitter thread from a Washington Post reporter drives the point home, and says we must fix this by being radically transparent about what we do.

common thread in many of these bad faith attacks on press are that they seek to exploit public's misunderstanding/ignorance of how we do what we do. for a long time I've thought media's biggest mistake is assuming our audiences understand journalism conventions/how we do our jobs

— Wesley (@WesleyLowery) November 29, 2017

Another example: The New York Times does a lot of complex data science with election forecasts. Their prediction models are hard for anyone without a statistics degree to understand. So they created a page that explains how their models work by letting readers make their own, tweaking the different parameters to see what comes out.

This is what Jay Rosen, a journalism scholar at New York University, calls “show your work”. It’s about truly embracing the primacy of transparency in everything a journalist does. It’s about dropping the voice of god, the view from nowhere and proclaiming: we are human. We have biases. We make mistakes. Here’s how we do our jobs. We know you have concerns and anxieties. Help us do better.

This is hard. It takes humility, which is a slow quality to foster. It takes a cultural shift that has to come from the top. But more and more journalists are stepping up to the challenge. I’m certainly trying in my work

But so what? This all sounds very nice. But the burning question remains. Will this restore faith in the truth? Will these efforts make us once again share a set of facts so we can continue to progress as a society?

I wish I had a clear-cut answer. But even my deep-seated cynic has trouble seeing fault in this. It seems to follow so much of what we know about trust: that to receive it, one must give it generously. That no one likes a blowhard and a haranguer, and that people have a hunger to connect, to engage, to participate.

The popular web comic The Oatmeal has a great piece precisely on the backfire effect. I urge you all to read it. But I’ll spoil just the end, which I found inspirational.

The author says:

This universe of ours is achingly beautiful. And we’re all in it together. We’re all going the same direction. I’m not here to take control of the wheel. Or to tell you what to believe. I’m just here to tell you that it’s okay to stop. To listen. To change.

I hope us journalists, and all of us who work for the truth can lead by example.

Thank you again for inviting me. I wish you a great conference.